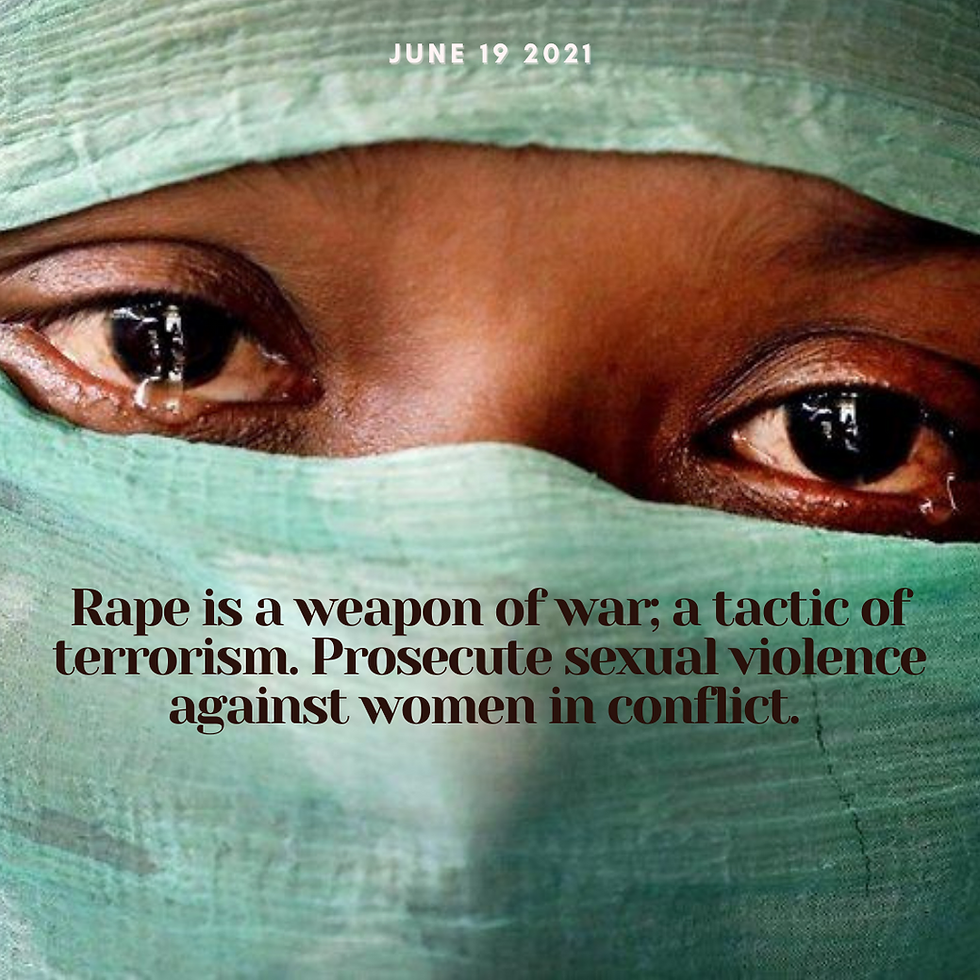

June 19 International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict

- Su Lee

- Jun 18, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 14, 2022

According to the 12th report of the UN Secretary General on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), 2,542 cases of CRSV occurred in 2020. However, this is a gross underestimation, since it is impossible to grasp the true extent of CRSV due to social stigmatization of victims, loss of evidence in war, and a general lack of functioning national institutions that investigate CRSV. In addition, covid-19 has exacerbated the impact of sexual violence in conflict zones with the closing of shelters, lack of medical aid, and less surveillance within these regions to monitor human rights abuses.

June 19 commemorates the adoption of the UN Security Council resolution 1820 (adopted on 19 June 2008). The resolution officially condemned sexual violence as a weapon of war, stating that “rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute a war crime, a crime against humanity, or a constitutive act with respect to genocide.” It also emphasized the additional attention needed for women and girls in “refugee and internally displaced persons camps,” as they are at greater risk of sexual violence. The resolution 2331 (adopted on 20 December 2016) highlighted emerging concerns related to CRSV in the modern age, especially human trafficking by terrorist organizations. Despite these recent headways codifying what sexual violence in conflict zones look like, women and young girls in conflict zones still face an onslaught of brutal abuse on a daily basis with no method of receiving medical care or redress.

Sexual violence in conflict takes make forms: brutal mutilation of female body parts, forced marriages, gang rapes, sexual slavery, human trafficking. The majority of CRSV are carried out by local militias, terrorist groups, and government officials, leaving women powerless to defend themselves against such widespread and pervasive threat.

Here are some examples of critical human rights abuses against women in conflict zones in the year 2021.

Syria: Although the threat of ISIS has begun to subside, thousands of Yazidi women have been abducted and subject to rape, torture, and other forms of physical abuse on a daily basis. Even those in refugee camps along the border have been subjected to sexual violence. Daesh has not been prosecuted for their sexual crimes. By prosecuting members of the terrorist organization for their sexual crimes, the Yazidi women have an opportunity to testify to the international community against their oppressors, which is an opportunity for the reclamation of their autonomy and dignity. The Yazidi women, one of the many ethnic minorities ISIS targeted during the brutal civil war, needs urgent medical and psychological care as well as safe zones away from the threat of additional sexual violence. The mass rape of Yazidi women can be seen as an example of sexual violence in ethnic domination to induce compliance.

Ethiopia: Tigray is one of 10 semi-autonomous federal states divided along ethnic lines in Ethiopia. In November 2020, the federal government of Ethiopia declared war on the region of Tigray. Amidst this fighting and the pervasive threat of covid in the second most populous African country, grave human rights abuses are going unnoticed. Tigrayan women are gang raped, tortured and mutilated. The majority of these rape victims described their attackers as either Ethiopian or Eritrean soldiers. For example, a 27-year-old woman in Tigray said she was repeatedly raped by 23 soldiers who threatened her with a knife.

Myanmar: Since the active persecution by Burmese security forces began in August 2017, around 600,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh. As part of the Myanmar government’s systematic persecution of the Rohingya population, sexual violence against Rohingya women and girls has been just one of the many methods of terrorizing Rohingya communities.Many women and girls in Rohingya villages have told horrific stories of being rounded up, raped, strip searched, sometimes in front of their families. The vast majority of sexual violence is conducted by official military personnel, who are rarely held accountable for their crimes.

South Sudan: The South Sudanese Civil War began in 2013 between the government forces led by President Salva Kiir and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition. After an estimated 400,000 deaths in the brutal civil war, 2018 saw the deescalation of conflict and steady peace talks. All parties of this war have committed acts of sexual violence. Between January 2018 and January 2020, UNMISS documented 356 incidents of CRSV involving at least 1,423 victims, most of whom have no access to adequate medical care or any mental health services.

Democratic Republic of Congo: According to the 12th report of the UN Secretary General on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), the Democratic Republic of the Congo has the highest number of CRSV with 1,053 reported cases. A majority of these cases were perpetuated by non-state actors, but there were still many cases of CRSV by the Armed Forces of the DRC and national police. Armed groups have also used rape as a tool to gain control of natural resources in North Kivu. Some perpetuators have been tried for their crimes: the former leader of an armed group, Takungomo Mukambilwa, was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison for crimes against humanity, including rape and sexual slavery. However, the majority of victims of CRSV will never be able to see their assailants face punishment. The DRC has been the rape capital of the world for the past decade, with thousands of faceless victims unable to report incidents in the fear of community backlash.

Sexual violence in conflict was part of wartime history for a very long time, including the Comfort Women raped by the Japanese during the Pacific War, the Bosniaks raped by Bosnian Serbs, and Abu Gharib prisoners in the Iraq war who were brutally abused by American soldiers. Both terrorists and governments have used systematic rape as a method of repressing and humiliating communities, suppressing their will to fight, threatening relatives and families, and often times, a tool of ethnic cleansing. The prevalence of rape culture in war zones will only subside when there are investigations and harsher punishments for perpetrators of sexual violence; until there are rigid frameworks for punishment, sexual violence will always be part of war. In addition to more support for victims through medical aid, one-stop centers and shelters, legal support, educational opportunities, the UN Security Council should begin to use sexual violence as an independent criteria for the implementation of sanctions. For far too long, rape has been a cheap and effective tool to instill fear in communities. Only when CRSV is treated more seriously with the ability to pressure and prosecute perpetrators, is rape no longer cheap.

Sources:

Comments